Welcome to the second part of this article about my top 10 imaginary worlds. Imaginary worlds are very real to their enthusiasts. While I would never wish to question the reality of millions of French, Spanish, Italian or American people, or the inhabitants of any other country I’ve visited, there’s a sense in which my tourism in those places has been no more real than my visits to Middle-earth, Arrakis, Skyrim or Earthsea. It’s a question of immersion, and of presence. Sometimes, when I’m reading a book, watching a film, or playing a game, I can find myself relating to its world from the perspective of a native. The worlds themselves may be imaginary, but that experience of being there, of being present in the place, is as real an experience as any.

For me, it takes a particularly compelling world to elicit that kind of a response. It needs to combine a detailed, fine-grained construction, with a vividly evocative mythic character—I need to believe in its legends, and also its cheeses. If its smiths make swords by casting iron in an ordinary forge, or its archers walk around with their bows permanently strung, I’m walking away—but if it gets all that stuff right, and then presents me with a dry and technological ‘magic system’, that bears no resemblance to any real world magical or ritual tradition, I’ll be equally incapable of becoming immersed in it. This is the combination that is nailed so precisely by the creators of the worlds in the top half of my list. The lives of their societies are, without exception, founded on a real understanding of how real-world cultures evolve in and through history, and their material details are imagined with equal rigour. In fact, the one is not unrelated to the other—any culture’s mythology is rooted in its material culture, and vice versa. These worlds have all been imagined in the round, as concrete geographies animated by human lives and imaginations.

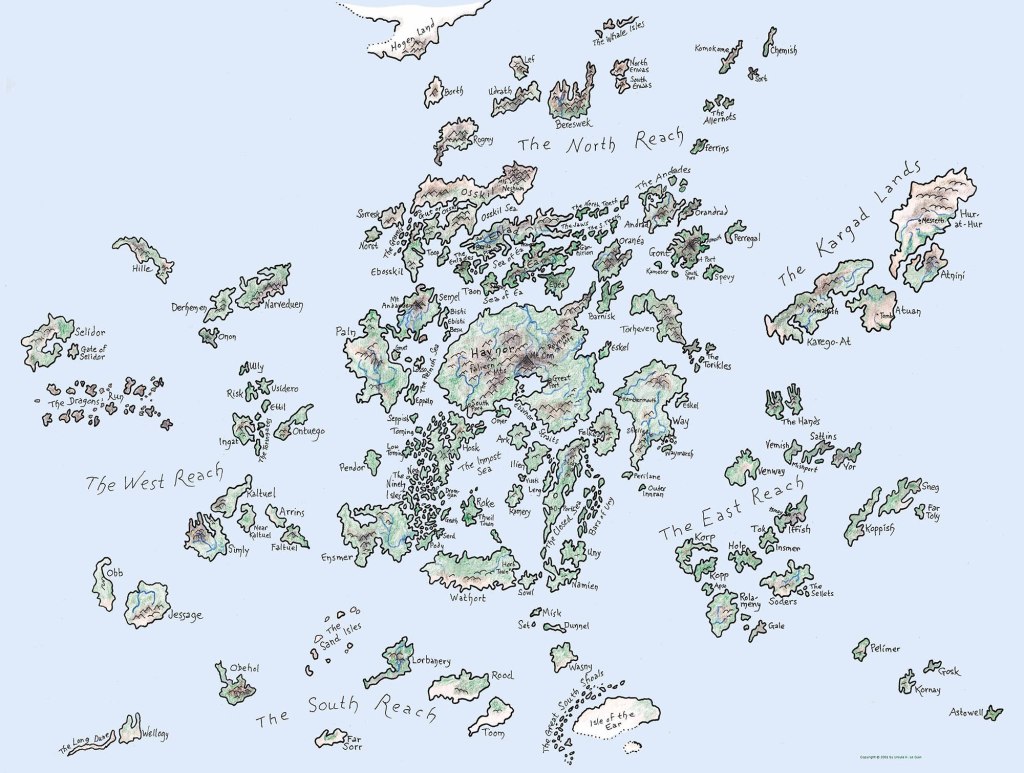

5. Earthsea

This was the start of it all for me. It’s an arguably bizarre decision to read a book that gets as dark as A wizard of Earthsea does to a six-year-old child, but that’s what my stepfather did to me. I will be forever grateful to him. At the time I probably didn’t have a firm grasp on the idea that some stories are set in the ‘real’ world, and other stories are set in imaginary ones. As a consequence, I still have no firm grasp on that distinction, and enter into fantasy settings with what some might regard as unhealthy abandon.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea is an archipelago (with some indications of larger land masses at its eastern edge, but these are never visited in the published stories). This offers Le Guin the opportunity to build a portfolio of cultures that are both more maritime, and more precarious than those found in most fantasy worlds, clinging to small scraps of land, and shaped by the defining presence of the sea. Not that there were many fantasy worlds for comparison at the time of A wizard of Earthsea’s first publication in 1968, and the publishing genre that we call ‘fantasy’ was arguably not yet fully in existence. Le Guin’s obvious and acknowledged influence was J.R.R. Tolkien. In fact, much of her early science-fiction has an epic, mythopoeic quality that is redolent of The Lord of the rings, and she seems unique among fantasy and SF writers in finding a jumping-off point in Tolkien for truly distinctive and original work of her own.

Earthsea is not at all like Middle-earth. It’s the work of a socially progressive, atheist, anarchist writer, and as such its mythological foundations are not authoritarian religious ones. Magic is the marrow in its bones. Alan Moore has often spoken about the relationship between magic (he is a practising ritual magician) and storytelling—or art in general. The latter is, for him, an example of the former, and Le Guin integrates a very similar insight into her worldbuilding. The magic of Earthsea is its language. The true name of every person or object in the world is its magical essence, which makes magic something that can be taught systematically, but also something that can never be separated out and treated as a purely instrumental technology.

Earthsea is populated largely by people of colour, and its cultures tend not to be built on the same assumptions as medieval European ones, although some of them are hierarchical, and some of them are violent. She said later that she regretted not having the courage of her convictions, and going further with her progressive vision. The early stories are about a heroic, male character, doing various heroic, world-saving things. The later ones are meditations on aging and domestic life, embodying women’s perspectives. As such they make a world in the kind of concrete detail that just bleeds off the page and leaves its grit beneath your fingernails.

4. Urth

Beginning in 1950, Jack Vance developed a fantasy setting known as The Dying Earth, set in a future so distant that the sun is dim and red, its final extinction imminent. The stories he set there were hugely influential. The original Dungeons and Dragons magic system was lifted straight from them, and many enduring fantasy tropes are first found there. In 1980 Gene Wolfe published The Shadow of the torturer, the first in a long series of novels set in a far future directly inspired by Vance’s work. Vance wrote beautiful, witty, entertainingly convoluted prose, which contrasted starkly with the workmanlike language of many of his contemporaries, but his Dying Earth stories lack any overweening ambition or pretension—they are satirical, picaresque adventures intended to divert and amuse their readers. Wolfe took that approach to language, and doubled down on its obscurantist qualities, while weaving a complex thematic and philosophical tapestry through the work that was inspired as much by Jorge Luis Borges and other high-fallutin’ modernist or experimental literary figures as it was by any genre writer. In The Encyclopedia of science fiction John Clute calls him ‘quite possibly sf’s most important author’.

There’s a great deal that I could say (probably incorrectly) about Wolfe’s writing, but I’m here to talk about his worldbuilding, specifically that to be found in The Book of the New Sun (the tetralogy that started with The Shadow of the torturer) and its sequel volume, The Urth of the New Sun. The dimly lit and fabulously ancient Urth in which those stories are set is an accretion of historical and material detritus. Mining on Urth is what we call archaeology today—no mineral resources remain to be extracted, but dig down a few feet in most places and you will find the abandoned wealth of a thousand forgotten civilisations. The human race has gone out to the stars and conquered them, built vast empires, brought unimaginable wealth back to Urth, and ultimately forgotten both the technology that enabled it to do so, and the fact that it ever possessed it. Wolfe uses archaic words, or words for archaic things (such as dinosaurs and other extinct megafauna) to describe things that have no exact equivalent today, mostly because their origins are extraterrestrial. The technological past is everywhere, but nobody knows what it is. Rusting spacecraft are used as buildings. Terrifying energy weapons are carried by fur-clad pikemen. Nothing is what it seems, and that is also the tenor of the narrative, in which apparent antagonists turn out to be patrons, and vice versa.

All of which sounds like a lot of great ideas for a world, but offers no guarantee of its quality. Well, Wolfe is extremely interested in making it real, and he rigorously imagines the kind of society that might arise in these circumstances. The story appears to be an episodic fantasy narrative, and it’s really only at the end that the reader comes to understand (if they’re paying close attention) that the whole thing is ‘fully arguable in sf terms’, as Clute puts it. Wolfe builds a complex, apparently pre-modern society, in the ruins of all the science-fiction futures that could be imagined, and he builds it not just from politics and histories, but from the everyday lives of the people who live in it. There is no aspect of it that he doesn’t think through, and the result is as internally consistent and as plausible as any imaginary world I’ve encountered. I first went to Urth as a teenager, and I had very little idea what was going on there, but I loved the complete mystification that Wolfe provided more than I had loved any reading experience in my life. The world is a very complex and confusing place, and it’s precisely that real-world kind of bewilderment that I found in Urth. There’s an awful lot you won’t understand, but it’s abundantly clear that it’s because you the reader don’t know how the dots connect, not because Wolfe hasn’t joined them up. Like everything else in my top 5, it’s the work of an absolute master.

3. Always Coming Home

That’s right, Ursula K. Le Guin appears twice in my top 5. That’s because she does the things I value the most in worldbuilding better than anybody else. If this was my top 10 favourite worldbuilders she’d be at the top of it. In Always coming home she not only builds an amazing world, but she presents a manifesto for worldbuilding. She was a prolific non-fiction writer, and her thinking emerges across a whole array of texts, but one in particular that seems relevant to Always coming home is The Carrier bag theory of fiction. In that essay, Le Guin builds on feminist theorists who argue that the archetypal and foundational human technology is not the long, pointy weapon (e.g. arrow, spear), but the round, encompassing container (e.g. basket, bag). I won’t bother to belabour the gendered symbolism of these ideas, but she considers their applicability to stories. The linear narrative, she argues, is not superior to a more spatialised collection of texts. She refers to the linear narrative as the ‘killing story’, as that is so often its end; the spatial collection is equivalent to home, to habitation, to maintenance, to repetitions, cyclicities and return.

It might be observed that The Lord of the rings is a story about coming home, not about going out and killing the bad guy. I’ve spoken about Tolkien’s influence on Le Guin, and Always coming home is something of an apotheosis of that idea. Short of a role-playing game sourcebook, there can be few published fantasy or science-fiction texts that more closely approach the archetypal technology of the bag or basket. The book consists of a number of meta-textual stories, poems, songs and other writings ostensibly produced by the culture that she invents, along with a number of essays written as though by an ethnographer from our own time and place. There is one longer narrative (a story of exile and return, natch) that appears in several chunks among the other texts, but it wouldn’t be true to say that the other things exist to scaffold or illustrate that narrative. Always coming home is a bag, in which Le Guin placed the language, cultural practices and mythologies that constitute a culture that ‘might be going to have lived a long, long time from now in Northern California’. This culture is called the Kesh, and it lives in the Napa Valley, where Le Guin’s parents owned a ranch.

Few writers have developed a grammatically complete and fully functional language as part of their worldbuilding. So far as I know, this exclusive club includes J.R.R, Tolkien, Suzette Haden Elgin, M.A.R. Barker (discussed in part one), the almost unknown Lorinda J. Taylor, possibly Arkady Martine, (also myself, but that’s another story), and Ursula K. Le Guin in Always coming home. This, for Le Guin, was not a question of encyclopaedic completism. The book isn’t that long, and it doesn’t go into that much detail (although it does go into quite a bit). What it tells you, is what it is that makes the Kesh who they are. This is not a simple thing. Think about your own cultural identity. If you think you could easily explain to someone what it is that makes you Scottish, or French, or Jewish, or whatever it may be, then I suspect you’re prone to over-simplification. Le Guin made a language as a part of her answer to that slippery question, along with a nuanced and complex set of spiritual practices, based around what she calls a ‘working metaphor’, rather than a collection of deities. She succeeded in constructing a completely plausible and plausibly complete account of her invented culture’s essential character, and along the way she produced one of the most astonishingly beautiful and moving books I’ve ever encountered.

2. Dune

Frank Herbert’s Dune, like many of the worlds in this top half of my top 10, is one I came to young. For that reason it’s a yardstick against which I measure other imaginary worlds, which kind of guarantees it a high place. I never said this list was objective! Of course a lot of people agree with me about its worldbuilding quality, and I hope that now the movies have made it big news, more people will find their way to the book and discover just what a thorough job Herbert made of imagining it.

One of the things that Herbert thinks through with a care that had not really been seen in science-fiction, is the question of the political, social and cultural realities of a long-term, large-scale interstellar civilisation. Isaac Asimov had postulated a feudal/imperial basis for such a society in his Foundation series, and depending on what assumptions you make about travel and communication times, this seems a pretty solid idea. It’s certainly hard to see how a twentieth/twenty-first century style bureaucratic state could operate in those circumstances. Herbert takes this idea (and it has been suggested that he was responding directly to Asimov), and tweaks it, restricting certain technologies so that his central thought experiment can have an anthropological focus. He eliminates computers with a religious jihad in the distant past, and he eliminates firearms with a personal shield technology that stops fast moving objects. This enables him to take some of the parameters of European feudal and Renaissance societies, and extend them across thousands of years and unimaginable distances.

While he’s doing this broad scale stuff, he’s also drilling right down into the finest level of detail on one planet. This involves the disciplines of both ecology and anthropology. His desert planet of Arrakis is probably an impossibility—an entire planet of sandy desert, that is nevertheless able to maintain a climatic and gaseous equilibrium able to support human life. Obviously, the scientific understanding of climate and ecology has advanced considerably since the 1950s when Herbert was writing, but he’s actually not far off the mark. The water is there, it’s just locked away beneath the surface by biological mechanisms. Living on this world are a few people devoted to its exploitation, natives of the interstellar civilisation referred to above, and a surprisingly large number of ‘natives’ (obviously they are also human colonists, but their entire culture has evolved in situ). This native culture, the Fremen, is developed in great detail, drawing on both Islamic and Buddhist sources. In fact, his whole book draws on a large number of real-world mythological sources, but I simply don’t have the space to go into that here.

The book Dune, with its several sequels, is an exploration of philosophy, anthropology, politics, religion, tradition, gender, and many other matters. It also contains some wonderful writing. Herbert isn’t infallible—some of his dialogue can be a bit wooden for me—but he is able to turn a phrase of exceptional beauty, especially in respect of landscape. The book, and the worldbuilding that informs it, are both far too multi-layered for me to even summarise their contents here. What I can say is that he built a world so complex, atmospheric, and complete that it can absorb me as completely now, with all of my middle-aged armament of critical thinking and worldbuilding knowledge, as it did when I was twelve years old. And I haven’t even mentioned sandworms.

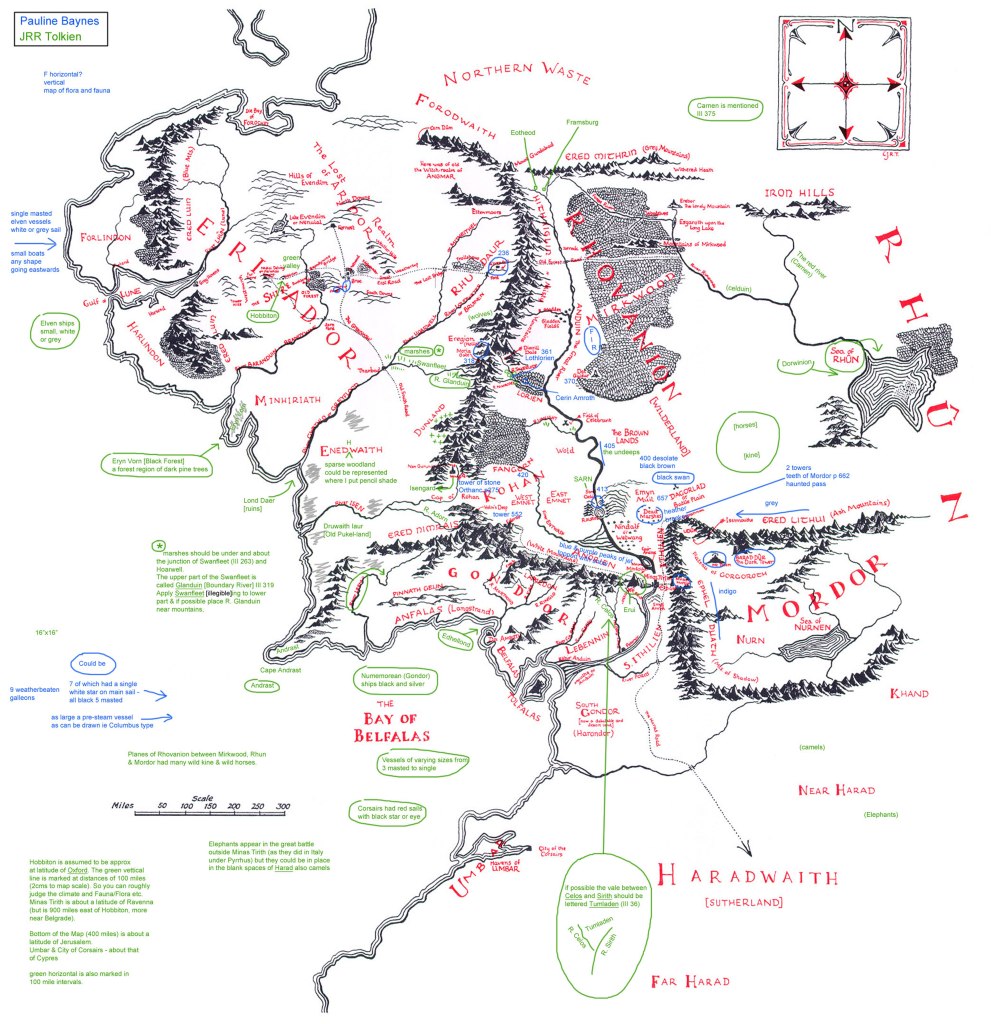

1. Middle-earth

It’s unlikely to be a surprise to see J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth at the top of my list. A lot of people agree with me, and anyone who knows me, or is familiar with my thinking on the topic, is likely to know of my admiration for this colossus of fantasy worldbuilding. I talked above about the quite intense experience of having A wizard of Earthsea read to me at the age of six. Well, I have the most incredibly vivid recollection from a couple of years before that, of my first encounter with Tolkien’s meisterwerk. Aged 4, I was staying the night with a friend. At bedtime, his mother appeared in his room to read us a story. I remember candlelight. I may be wrong, but at the time both my friend and I lived with our families in squats in London, many of which were in buildings without electricity, so it’s plausible. Either way, the lights were low. She was part of the way through reading him The Lord of the rings. What had possessed her to think that this was appropriate fare for a four year old child’s bedtime story escapes me. I guess she wanted to read it aloud, and lacked the patience to wait until he was a suitable age. The scene she read was the arrival of the Fellowship of the Ring at the Gates of Moria, and the events that follow. For the rare reader that knows neither the book or the films, this involves lurking terror, mortal peril, gigantic luminous tentacles, and a pony called Bill running off into the dark on his lonesome. These details remained imprinted on my memory for the four years it took before I read the book for myself.

When eight-year-old-me found that scene, it was a homecoming. And having read the entire thing at such a tender age, having had a part of it living in my heart already, I came home to Middle-earth. It could have been badly made, as imaginary worlds go, and the circumstances would still have made it compelling for me, but it was not—every hill in its landscapes has a history, every funny-sounding name has an etymology, every hobbit has an extensive genealogy, every line of verse has a Homeric epic behind it. I was completely convinced of its reality. I also managed to convince a number of my classmates, until my primary school headmaster became concerned and tried to put a stop to it. I remember angrily exclaiming ‘it’s not a game!’ when he raised his concerns in a school assembly.

I’ve said a lot about my making as a Tolkien fan, but relatively little about Middle-earth. Chances are you know a lot about it already, so it doesn’t seem necessary, but I will say a few things now. It remains one of the most well-made imaginary worlds, seventy years after its first publication. Many fantasy writers have been called Tolkien imitators, but they have largely just adopted some of his superficial decorative elements, such as elves, dragons, magic swords and extremely long books. Almost nobody has even attempted to tackle any of the things that makes Middle-earth so wonderful for me. First of all, the languages. It’s well-known now that Tolkien started as a maker of artistic languages, then developed a mythology to give them context, and finally produced fiction to give that mythology a life in the imaginations of realist characters. When I read The Lord of the rings that process wasn’t visible—all I could see was the fact that this world had its own languages. For a long time I fixated on this, as many others have, as the key to Middle-earth’s compelling character. I think it is a key to Tolkien’s deep understanding of the cultures he imagined, particularly the Eldar and the Númenoreans, but the most plausible account of the immersive power of the world as a whole I found in a paper by the Tolkien scholar Massimiliano Izzo. In explaining Tolkien too me, Izzo also explains the other worlds in my list.

Izzo talks about two strands of worldbuilding. There is the mythopoeic, which means the construction of imaginary mythologies, but Izzo also uses the term to refer to stories whose primary focus is on mythology, real or invented. And there is the encyclopaedic—the compilation of invented facts and details. He suggests that most commercially successful fantasy subsequently (especially epic fantasy) has been encyclopaedic in its worldbuilding, and that its mythologies have borne more resemblance to histories. The mythopoeic strand has produced critically acclaimed but less popular works, which tend towards a less detailed focus on the nitty-gritty of their worlds. This is absolutely key for me. The world I live in is one that is amply provided with both facts and mythologies. The imaginary ones I buy into heart and soul in are those that encompass both—and since Tolkien, the writers that have done that have not been numerous.

Tolkien built Middle-earth like a hard science-fiction writer. He was deeply concerned with making it materially plausible. Whether or not you think he succeeded (and there are certainly implausibilities in his socio-cultural imaginings), the deep, multi-layered mythic foundation that he built for his histories smooths the rough edges of his creation. After all, there’s a lot that’s implausible about the real world! And as he was a historian, he was able to make the history of Middle-earth resemble real-world histories. At the same time, he made a deep, broad mythology that lives vividly in the minds of his characters—a set of cultural materials from which his characters are made. Simply put, the whole thing has the ring of truth. For me, it is true. Not in the literal sense, but in the same way that a poem can be true, or that my love for my family is true.

In conclusion…

Perhaps if I’d gone with ‘the top 10 most popular imaginary worlds’ I could have written this article in one part, shorter than either of the two halves I’ve produced. But because these have been my top ten, I’ve needed to talk about my thinking in relation to each of them, and I do an awful lot of thinking about imaginary worlds (it may be an illness—can I get a somniomundopathy diagnosis?) It may be arguable that something along the lines of ‘Dune! Sandworms! Fremen! Ornithopters! Sword-fights! Super-cool!’ would have worked better. So perhaps what I’ve written tells you more about me than about the worlds I’ve covered. Maybe that’s not a bad thing. Hopefully, it’s been thought provoking. If you found novel ideas here, or worlds you’ve not yet visited, or just some reading pleasure, then my work is done. If you found none of those things, well, I’ll try to do better next time.