This is a blog about writing, but it’s about the specific aspects of writing that I’m most interested in. Probably top of that list is worldbuilding. In fact, I’d go so far as to say I’m interested in worldbuilding first, and storytelling second—although I’d also suggest that you can’t do one of those well if you do the other one badly. That’s a discussion for another, more theoretically inflected day, however. Today I’m keeping things simple, and I’m going to offer you a rundown of my top ten imaginary worlds. That’s kind of a huge topic for me, so in order to have the space to say what I want to say about each of them, I’m going to tackle the subject in two halves, with my top choices in second instalment.

I’m limiting myself largely to the genre of fantasy, rather than science-fiction, in order to make this an achievable project. I’ve made an exception for Dune, as that’s a place I’ve lived in my imagination since I was eleven years old. I’ve also made an exception for Gene Wolfe’s Urth, which appears to be fantasy at the outset, but is arguably SF once you know what’s happening (if anyone knows what’s happening in a Gene Wolfe book!) And I haven’t made an exception for Star Wars, because although I’ve been immersed in that universe for even longer than Dune, it’s basically a visual immersion. The Star Wars setting is so beautifully realised from a technical point of view that it’s almost impossible not to believe in it (especially if you’ve been visiting it since you were seven years old, as I have), but once you start to ask any difficult questions about travel times, society, economics, technologies, or really anything at all, the whole thing falls apart. It is what it is, but the kind of imaginary world I’m interested in here is one with a bit more internal consistency. Many other, predominantly cinematic or televisual worlds have been ruled out in the same way.

You might also think that role-playing game worlds are over-represented here. That’s just a question of the shape of my own personal journey, and doesn’t imply that I think they’re better than worlds from other sources, or more interesting. I just happen to have visited them more. I wouldn’t claim for a moment to know what the ten best fantasy worlds are, and I’d be very suspicious of anyone who did. For one thing, every reader (or viewer, or player, or listener) will have their own preferences, and at the end of the day what makes one individual really vibe with a setting is going to be extremely personal. For another thing, nobody knows them all, even scholars whose business it is to study worldbuilding. What I can do, though, is list the ones that have had the biggest impact on me, the ones that have resonated most fundamentally with my own sense of reality, and talk a little bit about why.

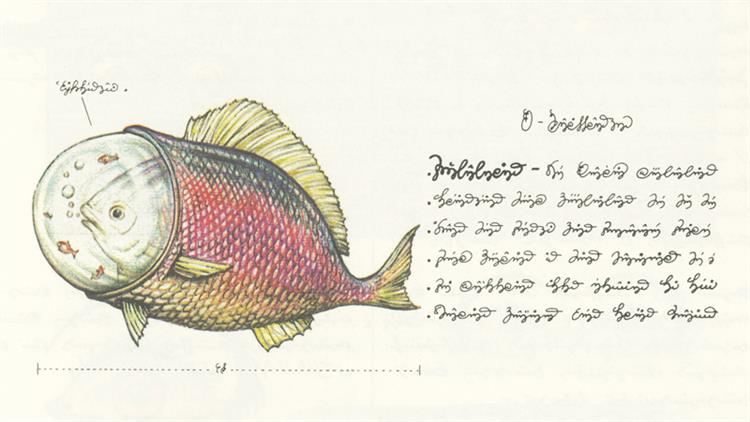

11. The Codex Seraphinianus

Yes, you read that right. In my top 10, this is number 11. This one is a bit of an outlier, but I’m tacking it onto the start, because I couldn’t help myself. It may be a stretch to describe it as a setting at all, and given my reasons for excluding Star Wars, it may seem strange that I’ve included it. The reason is that, although it’s almost impossible to say what anything in it means or represents, I have found it to be as coherent, as systematic and complete as any other world in this list. And more importantly, I’ve been as deeply immersed in it.

The Codex Seraphinianus is an encyclopaedia, consisting of page after page of incredibly vivid and detailed surrealist art, accompanied by reams of text in a completely asemic alphabet. Asemic means that it has no meaning—not that the meaning has not yet been discovered (although there is a busy online community attempting to discern some), but that it literally has none. The characters of the alphabet give a wonderful impression of being organised in the same way as those of a real language, but other than the numbers (it does include a consistent base-27 system of numerals which is used to number the pages) they do not signify. The images are incredibly detailed and varied, and give every impression of systematic representation of a completely impossible world. Luigi Serafini deliberately sets out to confound explanation or interpretation. He has said both that he wishes to create the sense for adults that young children have when looking at books they can’t yet understand, and that although you may think its speaking directly to you, it’s ‘just your imagination’. Think about that: ‘just’ your imagination. If you find meaning here, it’s because you yourself are creating it, and that’s a wonderful thing for a book to elicit. The book is almost impossible to describe (as you may have noticed), held in very few public library systems, and extremely expensive. When I finally bit the bullet and got myself a copy, I was not disappointed, and I’ve been an enraptured tourist in its world ever since.

10. Tékumel

I also had doubts about including this world, but for very different reasons. They have very little to do with its qualities as an imaginary world, and a great deal to do with the personal failings of its author. Some years after the death of Professor M.A.R. Barker, it was revealed that in the early 1990s he had written a novel of neo-Nazi sympathies under a pseudonym, and that for many years he served on the editorial board of an American far-right journal. When I discovered this, I was devastated—I felt it as an appalling personal betrayal, precisely because the world that Barker imagined is so wonderful, and I had been so deeply immersed in it.

There are really only two writers that I know of who have built imaginary worlds in the way that Barker did: the other one designed the world that is number one in this list. Barker was a linguist with a particular interest in South Asian languages, and he constructed several languages (conlangs) inspired by that linguistic milieu, before going on to design a complex world for those languages to live in. His was a science fantasy, set in a distant future, on an alien world colonised by humans, on which several intelligent species co-exist. I forget whether there was a pseudo-scientific rationale for the magic in his world, and I’m basically too sad about the whole thing to open up the books and find out. Tékumel primarily served as the setting for the D&D derived RPG Empire of the Petal Throne, a legendary 1970s game from the first generation of D&D imitators. Barker also wrote a few novels set there. I’ve read a couple, and they don’t set the world on fire as novels, but they do read as though they’re set in a real place, with all of the real world’s complexities and inconsistencies, which is not something I can say for many secondary-world fantasy novels, if I’m honest. For me, Tékumel is fantastically exotic (for its alien biologies, not its South Asian inspiration), detailed and immersive, and in the final reckoning it was impossible not to give it a place in this list.

9. The Continent

So here I have to fess up, and admit that I’ve not read Andrzej Sapkowski’s ‘Witcher’ stories—I know this world only through CD Project Red’s amazing series of action RPGs for PC and console. Sapkowski has not always had a perfectly harmonious relationship with CD Project Red, so I don’t know how faithful the game’s version of The Continent is to his writing, but it certainly possesses similar features to the ones his book is supposed to have.

Let’s start with what’s wrong with it. Every significant female character is tottering around on ridiculous spike heels, and cities are provided with brothels in which the player can trigger sexual cut-scenes featuring one of several nubile female character models. Several major women characters are sexually available to the (male) protagonist, Geralt of Rivia—in the main game of The Witcher 3 these liaisons make perfect sense in terms of the long-term story, but if you play the expansions you realise that the developers thought it was obligatory to put a good shag for Geralt in for the (presumed male) player to vicariously enjoy. However, those same female characters are one of the great strengths of the storytelling. They have their own agendas and narratives, in which Geralt features, but is not necessarily central, they are convincingly characterised, and they are (in the English translation at least) provided with some good dialogue and voice acting.

The world itself features here partly because I spent a long time in it, and had fun there, but also because it is one of the more plausible pseudo-Medieval fantasy worlds I’ve encountered, in games or in books. Most of its fantastical elements are based on Polish folklore, which gives it a unique colour among English language imaginary worlds, and aids its cohesion as an imagined culture. It represents the class structure of Medieval society well, and the people of The Continent are bound by their social obligations in a way that is often lacking from pseudo-Medieval worlds. The hero Geralt gets to wander from village to village having adventures because that’s his job, and his status as a Witcher brings its own set of obligations and responsibilities. It’s a gritty, muddy world, in which peasants mostly have a bad time, and in which war is no fun at all. Visual worldbuilding allows you to shortcut many important considerations regarding culture and society, but in this case those facets are usually plausible when they’re touched upon. The Continent is not a place I’d like to visit for real, largely because it is so real.

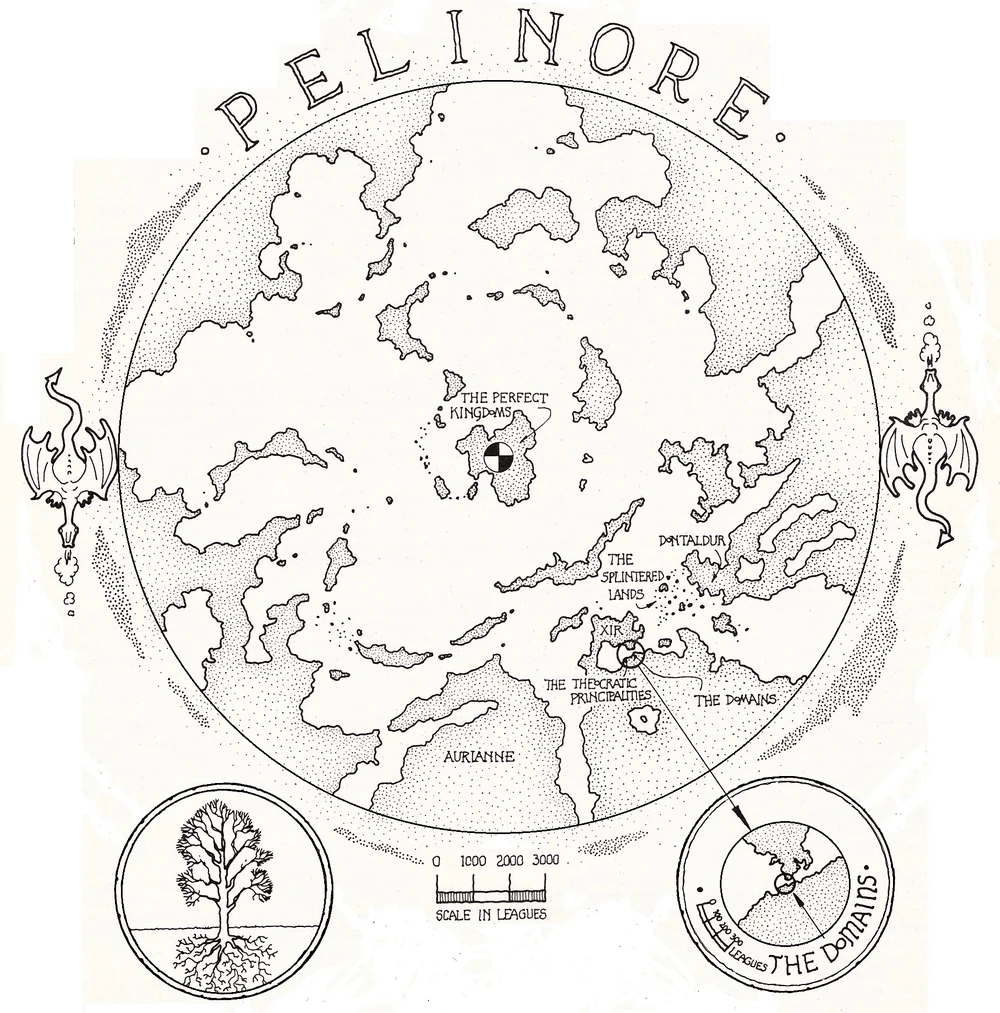

8. Pelinore

Of all the D&D settings I could have mentioned, why this one, which you almost certainly haven’t heard of? Because it’s the only one I ever bought into, heart and soul. It was originally published as a series of D&D adventure modules and articles in issues 17-30 of Imagine magazine. This was TSR UK’s monthly mouthpiece, and had a distinctly British flavour compared to their Dragon magazine (TSR UK was also responsible for the wonderfully inventive Fiend Folio bestiary supplement for the 1st edition of AD&D). After Imagine folded, Pelinore continued in the five issues of Game Master Publications magazine, and then it faded into (greater) obscurity, but it had left an indelible mark on me.

Again, there was a visual element to this. The Pelinore materials in Imagine were accompanied by beautiful maps and illustrations by the architecturally trained Geoff Wingate. As I understand it, Wingate did fantasy illustration and cartography for a very brief period in the early 1980s, then moved on to other things and never looked back, having no interest in role-playing games himself. In that short span of years he created a body of work which formed my view of what fantasy maps should look like, and had a considerable influence on later artists—the original Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay is visibly indebted to Wingate’s work on Pelinore, for example. His well-informed drawings gave the setting a sense of a coherent architectural vernacular—largely a late-Medieval/early Tudor sort of vibe, but with some less European elements as well. This was consistent with the writing for the setting, which combined the familiar with the exotic in a very pleasing way. I don’t make any great claims for this setting, which can be found compiled into a single PDF document of just under 100 pages, but it was very well designed, and felt much more plausible to me than Greyhawk or Forgotten Realms, or any of the other D&D settings I encountered.

I didn’t look at any Pelinore materials for several decades. I had a complete collection of Imagine magazine from issue 1 to issue 30 (the last), and for reasons that I find almost impossible to fathom, I threw them away in the mid 1990s. I think I was going through a phase of disavowing my younger nerdy self (and I did, to be fair, lack the space to store the things I tended to collect). I hadn’t looked inside them for many years by that point. Then I did a little research for this article, saw the stuff for the first time since the 1980s, and blow me if large parts of the fantasy world I’ve been working hard on since 2010 don’t bear a striking resemblance to bits of Pelinore—sufficiently so that it will warrant a mention in my acknowledgements. The material is still in copyright, but there’s really no way to get it that involves paying any of its creators for their work (and I don’t think Wizards of the Coast have the slightest interest in asserting their presumed rights to the contents of Imagine magazine)—so I’d recommend you do some internet searching, find the PDF, and have a look at this stuff. It’s really atmospheric.

7. Westeros

There’s really not much that needs saying about the world of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. It’s so well-known, and so influential, that the chances are, if you’re reading this, that you know more about it than I do. I should point out that I’m talking exclusively about the world of the books, not of the TV series. The setting of the books is in many ways the exception to the rule, in terms of epic fantasy settings—it is founded on a genuine interest in Medieval Europe, and the ways that its societies worked. All the things that are right with the books in this regard are wrong with the TV series, which just makes it all up off the top of its head and assumes its viewers will be too ignorant to know better.

Martin isn’t obsessive about his research or pedantic about the details—he just broadly gets what it meant to be a peasant, or a knight, or a merchant in the Middle Ages. He understands the web of social obligations and constraints that surrounded people in pre-modern societies, the omnipresent threat of violence, the bald and unapologetic basis on which social hierarchy was maintained. He also handles magic and the supernatural well, making it unusual, mysterious, and difficult to understand—it is never prosaic in his world, in the way that it is in many others.

He gets some things wrong, of course. Westeros itself (which I’m using in the heading as a metonym for his entire world) is basically Britain, with all of the distances multiplied by ten. This leads to a completely implausible set of relations between travel time, politics, cultural difference, the exercise of military power, and so on. Organised religion has a similar cultural role to Christianity in Medieval Europe, but completely lacks the political heft to make it matter—despite which, it sometimes matters anyway. However, these shortcomings strike me as forgivable, simply because every one of his vividly drawn characters gives every impression that they are the product of their culture and society. The world makes them, and they make the world—this for me is the greatest test of any imaginary world.

6. Glorantha

Top of the first half of my list is another game world, although it has had quite a lot of fiction set inside it over its nearly fifty-year history. Greg Stafford’s Glorantha is most famously the setting for RuneQuest, one of that legendary first generation of tabletop RPGs, designed by Steve Perrin et al. Like many of those early RPG publishers, Stafford’s Chaosium started out with a wargame, White Bear and Red Moon, which was later republished as Dragon Pass. This game was set in Stafford’s own imaginary world, which was kind of unusual for a wargame, and was followed in 1978 by RuneQuest. Again, this was a well-trodden path, inasmuch as the first RPGs grew out of tactical wargaming, and a desire to focus on smaller and smaller units. Stafford’s interests seem to have tended toward an even narrower focus, on the personal stories of each character—he went on to develop Pendragon, a narratively focussed game set in Arthurian Britain, and lent his world of Glorantha to Robin D. Laws’s HeroQuest, a game which sets out to favour player aptitudes in narrative improvisation rather than in strategy or maths.

I never played RuneQuest much—in fact I probably only played it twice. But I bought and read its supplements and adventures with alacrity, because it was just such a wonderful setting. I’ve always been that way—I don’t need to be told stories in order to get sucked into an imaginary world. Sourcebooks and maps will do it just fine, but it needs to be quite a world before I’ll buy into it. Glorantha grabbed me because it wasn’t a generic fantasy world. It was broadly a Bronze Age setting, and its various cultures were imagined from the ground up, rather than being based on some primary world nationality or other. As such, it doesn’t feel European—it has an exotic feel, in the most positive sense of that word. If I’m honest most pre-modern settings for fantasy games or stories strike me as misapprehensions of Medieval Europe, thinly veiled revisions of Olde England in which characters tend to relate to their communities and societies as though they were twentieth-century westerners. Glorantha feels genuinely other, and as such it’s far easier for me to imagine real people leading real lives in it, paradoxical as that may seem. Its all-pervading magical practices, its panoply of competing cults, its intelligent non-human peoples, all with their own distinct cultures, its complicated, messy histories, all come across as integral parts of the same vivid tapestry. The whole world is presented with wit and humour, but it stays on the right side of satire—it’s not a joke about fantasy worlds, in the way that Douglas Adams’s universe might be a joke about science-fiction worlds. It’s just full of the kind of absurdities that make our own primary world so bewildering and complex.

So, there you have it, the first half of my tour of invented places. There are many more than I have space to feature, many more that I am familiar with, and may even love. But this small sampling is the product of my own personal journey through the amazing and improbable landscape of the completely made-up. These are the worlds that have had a real impact on me, and they are, therefore, the ones that I feel qualified to say something about. A more systematic survey would suit a more scholarly context, but one thing I’m quite happy to have done here (and to continue doing to a lesser extent next time) is to feature some vivid and immersive locations that have received little attention, even now that imaginary worlds are seen as a valid subject of scholarship. Tune in next time for more impossible places!