In the first of an irregular series of interviews, I spoke to the horror and speculative fiction writer Priya Sharma about her working life as a writer. If anything has become clear to me in the time I’ve been taking an interest in writing, it’s that writers are an exceedingly diverse bunch of people, and that the ways in which they approach their craft are equally various. The focus of this blog is not intended to be a creative or critical approach to writing so much as a practical one, one which should be of use to both aspiring and practising writers—and who could tell us about the nitty-gritty of the writing life with greater authority than writers themselves? Bearing in mind the great diversity of writing, writers, and their lifestyles, I intend to speak to writers whose working and writing lives are as heterogeneous as possible. Hopefully, somewhere in all that variety, you will find an account that seems relevant to your own circumstances, or a description of a life-/workstyle that you can imagine yourself inhabiting.

Priya Sharma’s fiction has appeared in venues such as Interzone, Black Static, Nightmare, The Dark and Tor.com. She is a Shirley Jackson Award and British Fantasy Award winner for her short story collection All the Fabulous Beasts (Undertow Publications). Her novella Ormeshadow (Tor.com), won both a Shirley Jackson Award and a British Fantasy Award, and was a 2022 Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire finalist. Her stories have been translated into Spanish, French, Italian, Czech, and Polish. Her new novella Pomegranates (PS Publishing) was a finalist for the British Fantasy Award and Shirley Jackson Award and won a World Fantasy Award.

www.priyasharmafiction.wordpress.com

Do you write full or part time?

‘I write very part time.’

How much of your time do you spend writing?

‘I’m not someone who’s very good at having a set timetable for writing, so I don’t have an allocated time, ’cause there’s some days with work, you know, I go out very early, I come back quite late… I crash, I just haven’t got the headspace for it. Like most people I work… most of the writers I know, except for a small handful, have jobs as well, so it’s a very flexible thing for me. I remember reading… I think it was Dorothea Brande in Becoming a writer, who said you must stop whatever you’re doing at a set time every day and write for at least an hour, and if you can’t do that you’re not a writer, which put me into despair for quite a long time, because I felt it was quite hard-core, and I would never be able to do that in my life.’

That’s a very rigid requirement.

‘Yeah. I think her message is “have discipline and prioritise your writing”, but for me it’s very moveable. It might be twenty minutes a day, it might be an hour a day… if I’m on holiday I will write every day, and I will have an hour or so out of the day where I’ll just sit and write. I’m not the sort of person who, if you said “look, you’ve got eight hours now, you spend the whole day writing”… I would find that quite intimidating, I’ll be honest with you. If I know I’ve say got ten minutes, I’ll look at something and maybe do a bit of scene planning, or just sort of sketching out, or just a little bit of editing or revision—or research. But I wouldn’t say I’m very good at having a set timetable.’

How easy do you find it to get stuck in when you do get time? When you’ve got say, half an hour, do you find you can end up frittering it away?

‘Oh, I’m terrible, it’s one of the things that probably contributes to my small output, actually… Compared to a lot of people… I mean the American writer Stephen Graham Jones, I think at one point his editors and publishers had to slow him down, because he was producing so much work! I’m never going to be that sort of person. I’m very, very slow, very considered, and yes, I will procrastinate, and I think that’s the thing: you’ve got to learn what your weak spots are. If you’re better getting up in the morning and starting straight away, and you’re in the right headspace, then do it. If you know you’ve got a load of tasks to clear, and maybe you’re a night worker… I think you’ve got to work out what’s your optimum time for concentration, when you’re not going to be distracted, and where it is, you know. Are you going to be in the house, are you going to go out? Some people have to work at home with all their stuff around them. For certain projects I like to be mobile.’

So you don’t have a set of conditions or rituals that have to be followed for you to write?

‘I did, I had a point where I was thinking I had to work in a certain way, and I went to see the novelist and short-story writer Sarah Hall speak in Liverpool, and somebody asked “do you write with a pen or a laptop?” She said that it doesn’t matter, you shouldn’t get tied up on the process. Be flexible, and realise that every single project, and how you work from week to week, will be different, and that’s okay. So that made me think about my own personal magic, you know, “Dumbo’s feather”, if I had a certain pen and notebook I could write in a certain way—which was ridiculous, it was me procrastinating.’

How long were you writing before you worked that out? Did that realisation come around the time that you were first able to get stuff finished?

‘Well, no, that was just getting stuff started, Oliver! It took much longer than that, actually—to get stuff finished was the next big push. I had a lot of half-finished projects. I am a very slow bloomer. I’m pretty much self-taught, I never went to writing classes, I’ve got no formal writing education as it were. But I’ve always read a lot. I think that was how I learned. And I learned by mistakes.’

What job do you do to pay the bills? I know you’re a doctor, are you a GP?

‘I am.’

Do you find that has any bearing on your work, or on the way you work? I suppose it would be easy for a lot of people to think, ‘oh, you’re an NHS GP, no wonder you write horror.’

*laughs* ‘I think the thing about general practice… it’s interesting, I wrote a piece for Writers’ Mosaic [an online magazine and developmental resource focused on UK writers of the global majority] about medicine and literature, because there’s quite a few doctors who write. There’s Usman Malik, who’s quite a well-known, well-respected horror writer, John Llewellyn Probert, who’s a surgeon who writes horror, Vikram Paralka who’s a haematologist in the States, Eliza Chan is medically trained, so there’s quite a few of us. I think for me, the thing about general practice is… one of my trainers said to me once, “it’s an art, it’s not a science”. Obviously you’ve got to know the science, but when it comes to people, it’s a whole different craft, and you need to be interested in their stories. I think stories are the overlap here, between [writing] and general practice. You know, what is this person’s story? How is this problem going to affect them? How is this treatment going to affect them? It’s perhaps a more holistic view of people. Obviously, I’m not going to write something that somebody tells me. The consultation is sacrosanct, that relationship is sacrosanct. But at the same time, I think, in terms of being interested in people, and being very privileged to see people through some of the most painful times in their lives… I’ve read some stories by psychologists, and they’re always brilliant, because they’ve got a really great insight into human nature, and I don’t think you need to be a medic to do that… anywhere that you’re public facing, and you get to talk to people, will have that experience.’

I absolutely find that, working in a public library. I’m constantly brushing up against bits of people’s lives that I would never have been able to imagine.

‘And you will see the whole gamut of human experience. And you will see people, when they come to that library, to that public space—for me, going to the library, you’re going in search of something aren’t you?’

We’re a point of contact for a lot of services, and people often come into the library when they’re in crisis.

‘Yeah, that’s it, that vulnerability, and that’s a privilege isn’t it? To be able to be there for people, and hear their stories. Was it Margaret Atwood who said ‘we all become stories in the end’? That’s what we are. So for me that’s really important. I am interested in the anatomy and physiology of things, and all that kind of stuff, which crops up in some of my work as well.’

Having recently read All the fabulous beasts and Pomegranates, there are a few moments where you can see your medical expertise has informed what you’ve written.

‘Yeah, I love the science of it, obviously anatomy and the human body, but also birds, and seeds, and all the natural world stuff, all the ecological stuff, all the natural history stuff is fascinating. As I’ve got older I’ve got more interested in that, I think. So, it’s all mixed up, I’ll be honest with you.’

From a more practical perspective, your job is a notoriously stressful one. I think you told me before that you work thirty hours per week?

‘Yeah, roughly.’

So you’re not absolutely flat out every day, but would you say work makes it harder to get your writing head on, or is writing a welcome escape?

‘I think all of us, I think we have those days where we just think “I cannot face sitting down and doing anything”, because I feel full up, and I think we all experience that, don’t we? But there are times, especially when I’m at that magical point in a story where you know that the rust is coming off your cogs, and it’s starting to roll, and it’s gaining momentum, and you can almost see the finish line. It’s at that exciting point where, I always describe it as being at the top of the hill, where you can see the end, you can see the other side, but you can look back as well, and see the errors you’ve made on your journey and start to fix things. I love that point in a story, where it’s all starting to click, you know. For me, having the pleasure of that as a counterpoint… and when it’s something I’ve got to research as well, I really enjoy that, because it does take me out of myself.’

Yes, I’ve never spoken to a writer who didn’t seem to enjoy research almost as much as they enjoy writing.

‘I think the geek in all of us just gets very, very excited about that.’

Do you fantasise about writing full-time?

‘Now I know some full-time writers, no, in all honesty.’

You said earlier that being confronted with eight hours to write in is intimidating.

‘It is. I think I’m in a very privileged position, in that I can sell my work. Obviously I’m not a big cheese or anything, but I can sell stories now. But at the same time, I don’t think I’ve got the same pressure of worrying about paying my bills next month. As I’ve started going to cons and meeting people who are artists and writers full time… it’s a different beast, isn’t it? And a lot of them, that’s all they’ve ever known, whereas all I’ve ever known is having a steady job, and to make that leap, I think, would be quite scary. So I have every respect for them. And for some of them, having to present your baby to an editor at a big publishing company, and having them say “I don’t like that”—you know, that’s a year of your work.’

And when that has serious implications for your electricity bill, that’s a different story isn’t it? But there’s a big difference between being a full-time writer in that situation, and being a full-time writer like, say, Stephen King, where you can afford to think, ‘hm, shall I bother to write a novel this year?’ As a pure fantasy, would you like to be in that situation, where that’s all you have to do, or would you always want some other work in your life?

‘I think I’d need to have something alongside it, in that I love the idea on paper of being able to go off and write full-time, but I think if I won the lottery tomorrow and could do anything, I’d go back to university and maybe do a history of art degree, or something creative, like ceramics, or jewellery making, or silver-smithing—or history.’

I do feel like writing needs something to feed it.

‘Yeah, absolutely, I was going to say that. You can’t write in a vacuum. I think if you put me in a box all day and told me to write, I would struggle with that. You’ve got to fill the well.’

Do you have strategies to keep the creative juices flowing? Or do you just not write when it doesn’t seem to be happening for you at a given moment?

‘Oh, I think that would be dangerous, if I just didn’t write. I have spells between stories when I’m not writing, but one way around that is, as you’re writing and finishing up one project, to start working up the next one—just be it some notes, some research: put a little bit of time into what you’re going to start next. I think for me, that really helps me. And I think the other thing is—it’s quite interesting, because I had a job change last year, and I was listening to a lot of podcasts about coping with change, and one tip that I loved, and made a huge difference to me was the “fifteen minute rule”. If you’ve got something that you need to do—and you probably know this, ’cause you’re smiling—but if there’s something you need to do, and you’re procrastinating, just go and do fifteen minutes on it. And it doesn’t matter how bad it is, in terms of writing it doesn’t matter what the outcome of that is, if I’ve written a page of utter rubbish, I’ve spent fifteen minutes on it.’

So that you feel that you’ve actually made some progress, rather than it becoming a thing you’re frightened to go and face.

‘That’s it, because before you know it, fifteen minutes is half an hour, and it mounts up. And even if you’ve got a pile of rubble, you’ve got some bricks there with which to build—you know, just to get rid of the tyranny of the empty page. So that helps, and for me sometimes switching up location can help, just really obvious things like that. And sometimes, even writing the end, even though it’s never going to be a static thing, and I’ll change it. Or writing a scene in the middle—somewhere for me to hit when I’m writing. Because for me, I don’t know about you, but I don’t sit down and write in a completely linear way. Other people might, but I don’t, because I’m always thinking “but then if that happens there…”, and I’ve just read something that will inform the next scene, and then there might be steps where I have to go and fill in, and I think it’s not being frightened of that. Just to keep momentum going.’

But say you’ve got an hour, and you sit down to start writing, and you just feel ‘meh’, it really isn’t happening: will you walk away from it then?

‘It’s funny, because I’ve just started a draft over the last week or so of a new story, and I’ve had about four or five false starts. It’s been really bugging me, and today I’ve just sat down and said “okay, just do fifteen minutes on it.” And now, after all that, because I’ve been pushing it around in my head for a while, this story, only now do I know the angle. Before, I sort of had the characters, I had a little bit of an outline of where it was going, but I didn’t know the angle, I didn’t know how to enter that maze.’

You needed to maybe try a few things out.

‘Absolutely. Changing tense, changing point-of-view, but what I’ve done today will change the whole focus of the story, and the whole balance of the story. That’s fine: at least I’ve got something to go at.’

How much creative support do you feel from your professional network (e.g. agent/editor/publisher)? Do you get much input? Do you get useful advice?

‘The thing is, it works on loads of different layers. I mean, there’ve been times when I’ve been struggling with a story—’cause I never used to use other people before I got to the editor. Occasionally now, like, for example, I’ve written a story [which] is kind of a modern day witchcraft type thing: I’ve sent it over to a friend, Tracy Fahey [author of British Fantasy Award shortlisted collections The Unheimlich manoeuvre and I spit myself out] who knows all about folk horror. So sometimes using your friends who have got specialist knowledge in an area is really useful. A couple of times I’ve gone to friends like Penny Jones [author of collection Suffer little children and novella Matryoshka, both BFA shortlisted] or Alison Littlewood [Shirley Jackson Short Fiction Award winner, shortlisted for multiple awards and author of many novels, including her debut A cold season which was selected for the Richard & Judy Book Club in 2012] or Georgina Bruce [author of collections This house of wounds and The House on the moon, winner of the 2017 BFA for short fiction with ‘White rabbit’, and the funniest person on Substack] and said “would you just read this?” Because I feel like it’s not quite there and I can’t work out why, and somebody will make a comment that will just crack it open. So I think having people to bounce off is useful, and some people do that.’

It sounds as though you rely more on your peer group than your professional network.

‘No, I wouldn’t necessarily say that. I think I’m very lucky in the editors that I work with. Occasionally you’ll just need one or two comments from friends that will help push you along, even if it’s “look, this isn’t totally rubbish, don’t give up.” I’m very lucky in the editors that I work with, in that—I hope I’ve got to a stage where what I’m sending them is ninety-five percent correct, and they know that I’m amenable to comments, ’cause when they’ve come back to me and said “this doesn’t make sense to me, can you fix it?”, they know that I will go and fix it.

‘I wouldn’t want an editor sort of re-writing my work, because that’s my job, that’s what they’re paying me for. But ultimately I think a really good editor isn’t a copy editor, they’re not correcting your grammar, they’re actually looking at the shape of your story and saying “right, I love that element, and that element, but what’s going on there? You’ve not spelt that out, and I don’t understand where that thread gets tied up.” And they’ll have a proper discussion with you, because you’ll go back and say “actually, if you look down there, that’s where that ties in”, and they’ll say “well that’s okay, but dial it up”, or “dial it down”, or whatever you need to do with it… to me, a good editor is like having a free masterclass.

‘And if you’re working with editors that you respect, you like what they do, you like the anthologies they’ve put out, you like their work, and they can get on with you… I think there are certain things in a story that you need to fight for, but you don’t want to be difficult to work with. It’s a professional relationship, and you want to keep that going. I think it’s difficult. I was working in isolation, and it’s only been of late that I’ve had the confidence to show my work to my friends before it’s published. It’s strange, because some people have always worked in those networks, and having never been to classes or groups, I’ve never felt quite comfortable doing it, until now.’

What importance do you place on belonging to a community of writers? We’ve talked about how that can be useful to the writing process, but do you think of your work as being a contribution to a creative community?

‘I hope so. I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve made a lot of friends, and people are really mutually supportive. We all share resources, we all re-blog stuff. If we see a market that’s open people will share it, and generally people are really encouraging. At the start it was very much getting to know people in the UK, but there’s a wider sort of universal world-wide market [for] horror writers, and I think horror writers and genre writers are particularly supportive and friendly. So yeah, I mean, it’s lovely. There’s a whole social element to it. There have been times I worry, are we all just reading each other’s work, and it’s not getting seen outside of our peer group? laughs I mean, I hope it is! But yeah, I think belonging… we all want to belong don’t we? We all want to be a part of something. If you look at the UK there’s this amazing lineage, you’ve got writers like Ramsay Campbell and Clive Barker, I’ve met Ramsay Campbell at Fantasycon—and I know obviously British horror goes back longer than that—but to see those people around on the scene working, and still doing their thing, you know, they’re still loved and popular… to be a little footnote in all of that is lovely.’

How much time and effort do you invest in selling your work to publishers? Are you systematic about how you submit when you’ve got something finished?

‘Right now, because my output is so slow, I’m writing for people. When I started I had my massive big list that I worked down of where I wanted to send stuff, and some stories, in various incarnations, went round twenty or thirty different magazines, and then had a big cross by them on each [line] *laughs* But I’m fortunate now in that stuff is sort of spoken for, and I know that if they don’t ultimately take it, then I could maybe send it somewhere else. I mean, I have a blog, I have a Facebook page, I have an Instagram feed, but I’m not a massive hard-seller, in that I’m not constantly marketing my own stuff. I think that gets a bit dull. I know some people are slightly more business-minded, but I don’t enjoy that particularly. I’ve been lucky in that some of the places where I’ve been published do [marketing] very well—for example, at Undertow Publications, Mike Kelly, the editor, [is] really good at marketing, and put a huge amount of effort into that. Same with Tor, for one of my novellas… the push that they can give their publications is amazing. Obviously they’ve got a massive reach via tor.com because of Macmillan. PS Publishing obviously are really well-known in the UK, and have their own people who shop there regularly.’

How much do they want from you in terms of those marketing efforts?

‘It varies. I always try and contribute, I always try and do something myself, because I don’t think it’s fair, especially with the smaller presses, to put it all onto them. So I will actively try and get reviews, and ask people to review things, and try to ensure they’re put in the right place to be seen if I can. It’s hard, because obviously with the smaller presses you’d hope they’d invest some time into that for themselves, but I don’t think you can just leave it to them. I’m not entirely sure it’s fair, ’cause those people also have day jobs, families, and all those things, so I think you’ve got to hoof it a little bit for yourself. It’s not something I’m naturally very good at, I’ll be honest with you.’

The reason I read your work was because I saw you interviewed on a British Fantasy Society online symposium. That’s a marketing opportunity as much as everything else it may be, isn’t it?

‘Yeah, I was fortunate, in that they were running [a day] and they were looking for authors to fill it. I think sometimes it gains a bit of momentum, it gains a bit of ground, and you meet people through different bits of your lives, which can help. I was very lucky in that I was doing something with a film production company, and they invited me to Manchester, to Grimfest. I met some academics there. I love academics! They always interest me; you can do a PhD in Gothic Studies at Manchester University, so I got to meet some of the people that work there, and they took All the fabulous beasts for their Gothic reading group in the summer. You just meet people in different, odd little ways, and I think if you’re not hard selling, and you’re genuine, and you’re interested in them they’re interested in you. I don’t like hard selling people at all.’

It’s interesting isn’t it? I often see people posting on social media, ‘here’s my new book’ and so on, and I guess I do the same with my blog: ‘here’s a blog post’. But I’m very unlikely to actually click through and end up reading it unless there’s some kind of a personal connection.

‘Absolutely, and if you’re very aggressive with it, like “buy my book!”, nobody wants that, nobody wants to hear that. But because I was genuinely interested in them, and what they were doing, like one was really interested in J-horror, one was really interested in 1990s television, there was someone else who was interested in gothic horror, to meet them, for me, was a privilege. I was very fortunate, they said “well, have you got a copy of your book?”, and I said “if you don’t mind, can I give it you?” So yeah, it just sort of rolls out from there.’

Do you have any advice you’d offer to the up and coming writer about how to fit writing into their life, or about the writing life?

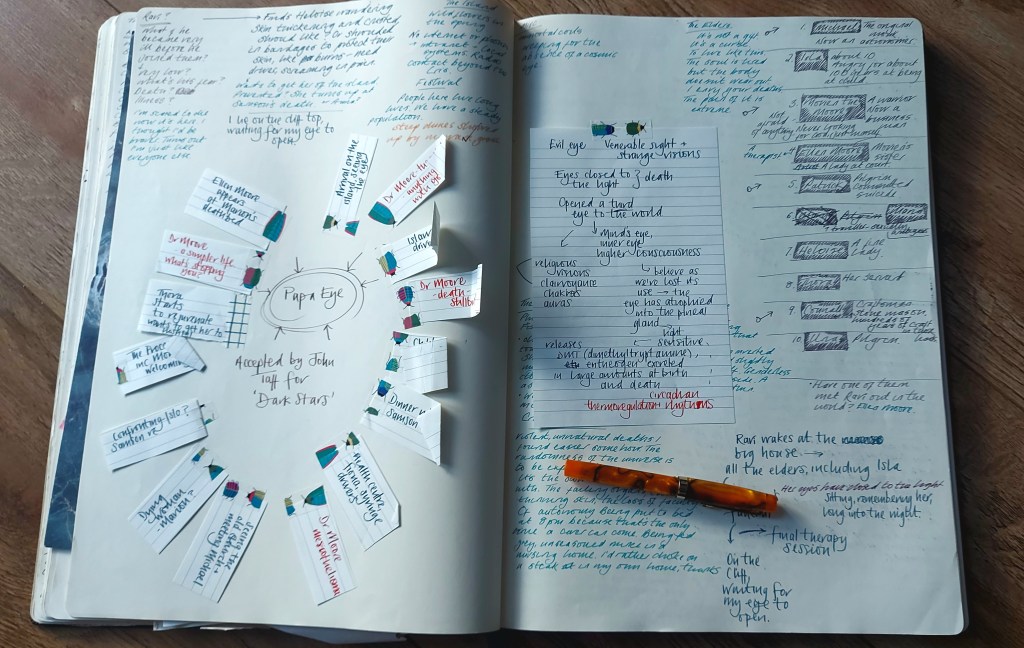

‘Look at the time you’ve got, be realistic—only Ray Bradbury can write ten thousand words a day, most of us are mortal—so look at the time you’ve got, look at how you can use it. It doesn’t have to be great swathes of time, it might be ten minutes a day, but if you can, just protect that time. Because often it’s just having that space in your head. Work out what time of day is best for you, work out how you work, because not everyone can necessarily sit at the typewriter and write in a linear way. I like to work at a big scale…’ *produces an A3 notebook with pages filled with visual plot diagrams etc*

Oh my god! That’s really interesting: you’re not pulling that out of your back pocket while you’re sitting in a café, are you?

‘If I want to take that with me, I photograph it, and just enlarge the bits that I want. If you’re not a linear thinker, if you think visually, if you want to draw a stick man and storyboard it, do it. There’s different ways of telling a story. You might want to walk along and dictate it onto your phone. Don’t be tied to a ritual, but also, don’t be tied to other people’s tyranny about what writing should look like. Because everyone’s on there posting that they’ve written five thousand words today, and my answer to that is “I don’t give a monkey’s”, ’cause I’m not that person. *laughs* It’s like that person that tells you what they’ve done in terms of studying for the exam: [it] scares the hell out of you. You don’t need to hear it.’

Yeah, I’ve written five words today, but they were really good…

‘Yeah! They were shit hot! And that’s all I needed to do. But your day might be thinking about one plot point, fixing one problem in your plot, and if you’ve done that you’ve done some work. Not all writing is at the page.’

Priya Sharma, thank you ever so much for talking to me.